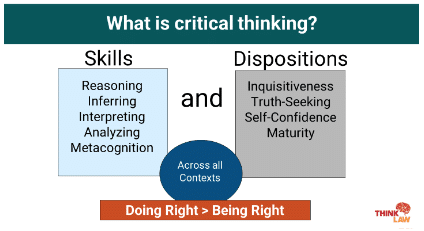

thinkLaw would not be much of a critical thinking company if we did not have a working definition of “critical thinking.”

In our work with educators and leaders all over the country, we often ask participants to define critical thinking. Most participants immediately respond to this question with a comprehensive list of critical thinking skills.

But the truth is: most students already possess critical thinking skills. The missing component is critical thinking dispositions.

Critical thinking dispositions are the habits and mindsets that cause people to apply critical thinking skills consistently throughout life, academics, and career.

Critical thinking dispositions are often the missing piece to our working definition of critical thinking. The difference between knowing better and doing better is often explained by the gap between critical thinking skills and dispositions.

We Were Wrong

What is a scientific fact that you were taught in school or by your parents that we know today is incorrect?

- Bats are not blind.

- One dog year does not equate to seven human years.

- Your tongue is not divided into separate sections.

- The seasons are not caused by our distance from the sun.

- Lightning can strike a place more than once.

- No chemical turns a color when someone pees in a pool.

We know that a key to 21st century success is the ability to learn, unlearn, and relearn. It takes critical thinking maturity for this to happen. We all internalize opinions and facts based on the information we have, but sometimes those ideas need to be adjusted when we are presented with the latest information.

Our society faces abundant problems when adults cannot accept added information to learn, unlearn, and relearn. So how can you develop this critical thinking disposition of maturity with the students in your classroom?

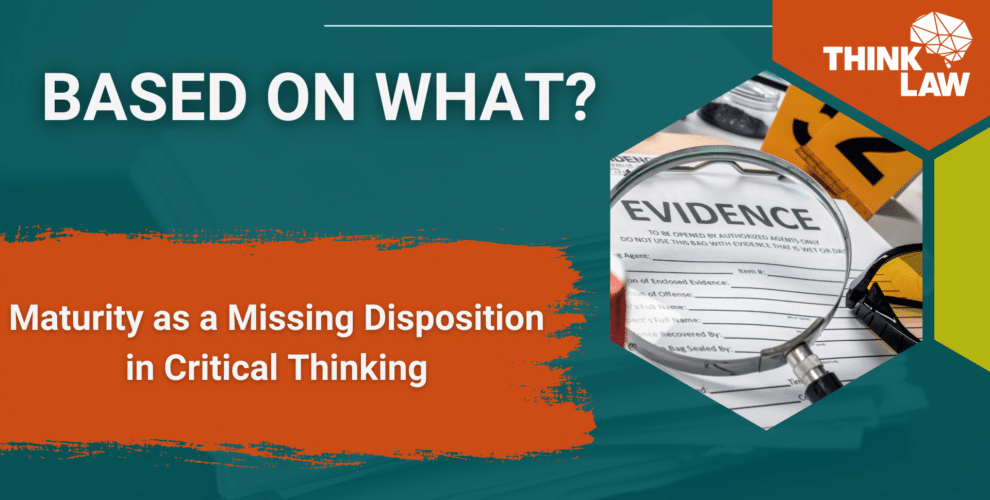

How Did this Impact Your Thinking?

In a thinkLaw Investigation and Discovery lesson, thinkers are provided with a tiny piece of information about a lawsuit.

For example:

A woman went to a St. Patrick’s Day parade. She was hit in the face with a cabbage and sued the parade organizers. Should she win? |

Thinkers are asked for their gut reactions. (For more information about using gut reactions in your classroom check out this blog.)

As the lesson progresses, thinkers are introduced to additional facts from the case.

| New Fact: Cabbages have always been thrown during this parade. Catching one is lucky. People want to catch them. The cabbage is considered a prize. |

Thinkers pause. How does this added information impact their original opinion in the case? This question does not have one “correct” response. Thinkers may feel this hurts the woman’s case. She should have known to look for cabbages. She probably wasn’t paying attention and got hit in the face, which makes it her fault.

The teacher continues to introduce additional facts from the case. Thinkers evaluate their stance after the addition of each fact.

- The cabbage was thrown overhand, like a baseball pitch, from the top deck of a two-story float.

- The woman suffered from a broken eye socket, cornea tear, and multiple fractures to her face.

- The woman needed multiple surgeries.

- The woman had over $75,000 in medical bills from the incident.

Everyone started the lesson with an initial opinion. As new information was presented, thinkers were asked to consider how each new piece of information impacted their thinking about the outcome of the case. At the end of the lesson, the thinker’s opinion about the outcome of the case could change or it could stay the same; either way, they have a more informed opinion.

In society, we tend to oversimplify complicated situations. Modifying your original stance with the addition of new information is not a simple matter of being “wrong.” You made the best decision you could with the information you had at the time. We need a generation of leaders, thinkers, and scholars who understand that sometimes an original position needs to change when new information becomes available. Practicing this strategy in a lesson allows thinkers to develop this disposition in a low-stakes way.

In Any Subject

Another quick way to practice this strategy in your existing curriculum is to introduce anything you are teaching one fact at a time. Rather than asking the class to read a full passage about the death of Caesar, organize it a little differently.

For example:

| Something happened to Caesar. It was a crime. You are the detective assigned to determine the motive. |

Introduce one fact at a time. Thinkers evaluate their stance after the addition of each new fact.

- Caesar became the dictator of Rome for life. He was the most powerful man in the world.

- Caesar appointed new senators. He replaced several greedy governors in the provinces.

- Caesar gave land to Roman soldiers and food to the poor.

- Caesar had enemies in the Senate who did not like what he was doing. They thought Caesar had too much power.

- Caesar invited Cleopatra to Rome to celebrate his victories. Caesar gave Cleopatra gifts and placed a statue of her at the temple.

Through this exercise, thinkers will change their answer. Perhaps the motive was a power grab. It could have been revenge. Now we have introduced a woman, and great romance can lead to great drama.

Simply restructuring HOW you are introducing the facts that you are teaching can have a powerful impact on creating critical thinking maturity by allowing thinkers to practice modifying their positions based on added information.

Join thinkLaw’s Tangible Equity Community on Facebook where educators are making an intentional effort to help thinkers become the change our students, school systems, and society needs.

Leave a Reply