The concept of data-driven instruction is relatively non-controversial. The idea of using data on student academic performance to guide instructional decisions is a bed-rock principle of modern education. But you make a significant decision when you decide how you interpret data and how you will teach students based on your interpretation. Data-driven instruction is not all that non-controversial when you RACK it up.

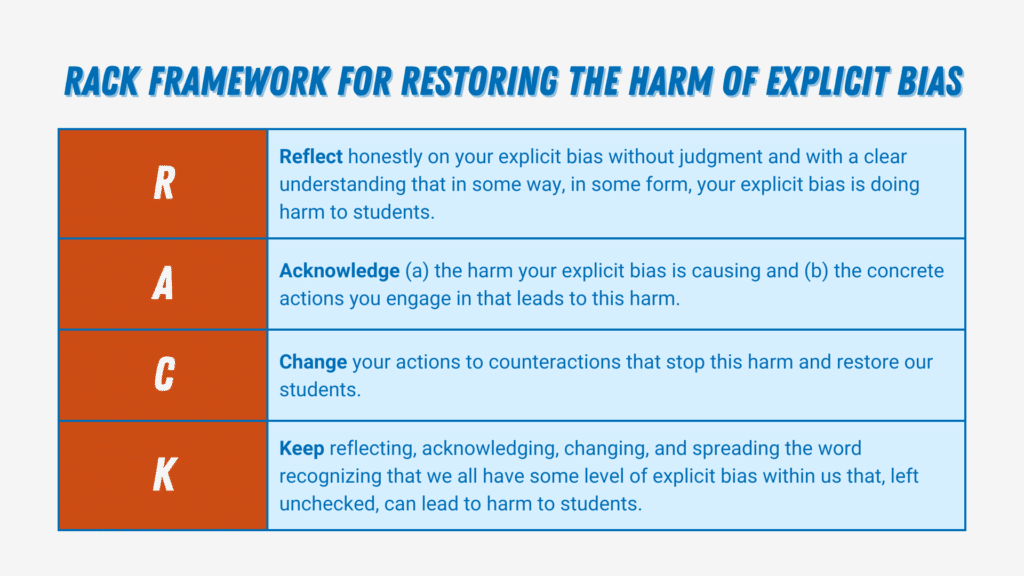

The RACK Process

RACK stands for Restoring the Harm of Explicit Bias. The RACK process recognizes that our good intentions are not good enough when our actual actions cause harm. I need to name that explicit bias does not necessarily refer to bias based on race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, or immigration status.

We can cause harm to students when we are explicitly biased towards students who share the interests we loved as children and against students who shared interests we hated. Try teaching a child with personality traits and behaviors that remind you of a child who bullied you growing up. Think about the explicit bias of teachers who struggle to name their own children because certain names bring to mind students who they would never want to conjure up when saying their own child’s name.

The RACK Framework involves 4 simple steps that require a fair amount of honest evaluation of the biases that exist within you and in your environment.

Step 1: Reflect

- Reflect honestly on your explicit bias without judgment and with a clear understanding that in some way, in some form, your explicit bias is doing harm to students.

Data-driven instruction involves a lot of subjective decision-making. It is easy to reduce students to a number instead of the full human beings they are. Every year I taught eighth grade, students scored miserably on the beginning-of-the-year diagnostics. I also noticed the same group of students forgot how to open their lockers even though they did so hundreds of times in the last two years. If my data probe leads me to an understanding that my students are “too low” to engage in rigorous, grade-level content, my data-driven decisions may result in an all-too-common lowering of the bar that ensures my struggling learners remain “low.”

Step 2: Acknowledge

- Acknowledge (a) the harm your explicit bias is causing and (b) the concrete actions you engage in that leads to this harm.

After you engage in the reflection process, identify the most significant ways your explicit bias is causing harm to students. In my first year of teaching in Washington, DC, my practice of treating students like data points did tremendous damage. My fear of “low” students falling behind forced me to teach the least-rigorous version of everything to the whole class. I left feeling like a clown when I learned that several of my “low” students were actually not “low” at all. They just rose to the level of my low expectations and stayed there. Even worse, my “high students” gradually lost interest because my data-driven decision was the starting pistol for a race to the bottom.

Step 3: Change

- Change your actions to counteractions that stop this harm and restore your students.

Change means that you are not just putting a stop to harmful conduct, but intentionally working to reverse it. To significantly raise the bar for students you once held very low may feel counterintuitive, but challenging your “low” students will also serve your “high” students. This shift in expectations for my students directly impacted their expectations for themselves in a way that transformed achievement more than my data-driven decisions ever would have.

Step 4: Keep

- Keep reflecting, acknowledging, changing, and spreading the word recognizing that we all have some level of explicit bias within us that, left unchecked, can lead to harm to students.

Once you realize that data-driven instruction is ripe for decisions grounded in explicit bias, you cannot “un-realize” that. Every piece of data – parent surveys, attendance records, standardized exams, even informal thumbs-up/thumbs down – lends itself to a RACK process. The process is not a straight line from point A to point B; it is a fluid cycle that requires each step be assessed frequently.

Tangible Equity is not about being a good person. It is not about having good intentions. It is about understanding that we are human beings with explicit biases that inform our decisions and our emotions.

Leave a Reply