In Chapter 16 of his book Thinking Like a Lawyer: A Framework for Teaching Critical Thinking to All Students, Colin recounts an exchange he had with his daughter after watching The Lion King.

Me: “Who was the bad guy in that movie?”My daughter: “Scar was the bad guy. He was really bad!” Me: “No, you are so wrong. Mufasa was bad. And Simba was the absolute worst!” My daughter: “What? Scar killed Mufasa, and he and the hyenas were messing up Pride Rock.” Me: “Mufasa was basically bullying the hyenas, and he gave Scar a scar for life in a fight that happened before the movie. He pushed Scar out to the edge of Pride Rock. And Simba—don’t get me started on Simba.” |

This quick and funny exchange can easily be translated into a classroom strategy.

Alexander the Great? Was He Great?

Across the globe students learn the story of Alexander the Great. But was Alexander great?

This is a question you can pose to your class. Take facts from your text and place each fact on a separate card. Have thinkers work in small groups to sort the cards into two piles: (1) Evidence that Alexander was Great and (2) Evidence that Alexander was NOT Great. This exercise will be trickier than it seems at first glance. Start with a fact that can fit in either category.

For example:

Alexander conquered more land and wealth than anyone before him.

- How could that fact support the idea that Alexander was great?

- How could that fact support the idea that Alexander was not so great?

As the teacher you should play devil’s advocate and question each choice. Depending on your class, you may assign a student in each group to object to each card placement.

Upon conclusion of the exercise, thinkers should have gathered enough supporting evidence to back their claims in answer to the question: was Alexander great?

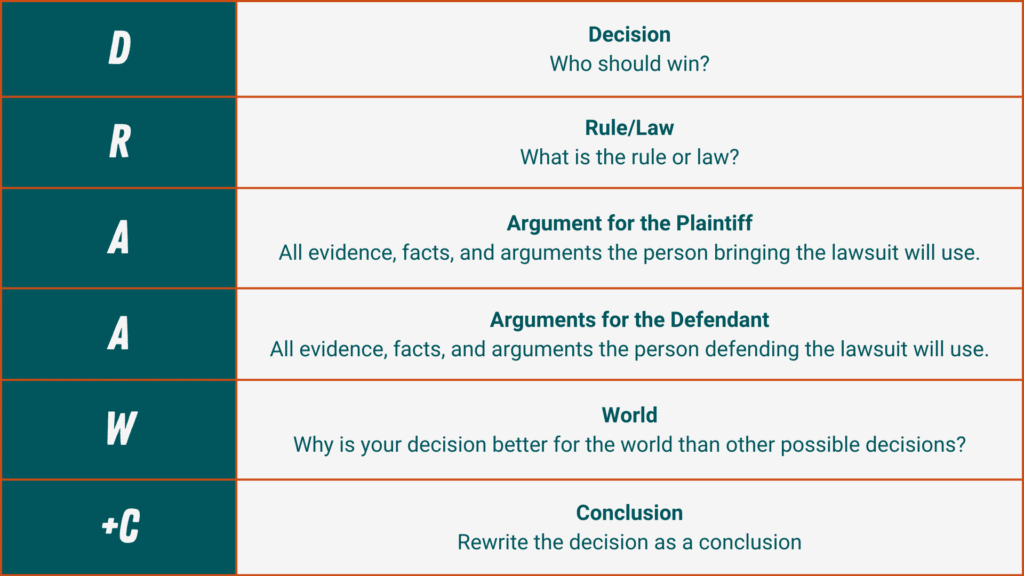

But how do students present their evidence, claims, and counterarguments in an organized manner? At thinkLaw we ask students to write using the DRAAW+C Framework:

Many persuasive writing frameworks ask thinkers to provide arguments from both sides. But simply saying one argument is right and one argument is wrong is an oversimplification of a messy world. Which side or decision is the best for the world? Why?

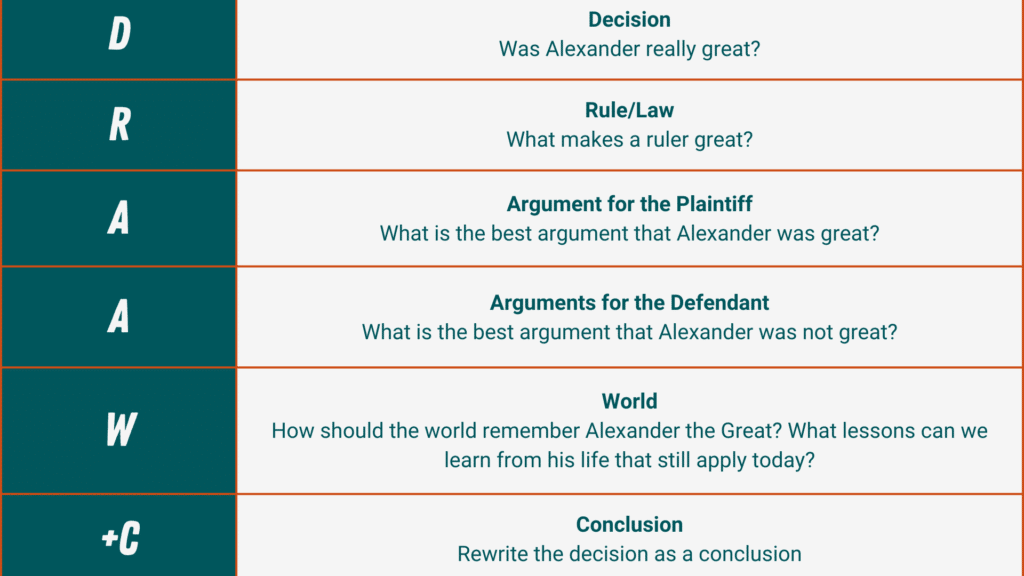

Here’s how the DRAAW+C framework would look like with our Alexander the Great evidence analysis.

This exercise can be completed with any famous leader throughout history, or even fictional characters. Let’s take a look at the antagonist in The Three Little Pigs, and how you can challenge young thinkers to consider the story from a different angle.

The Big Bad Wolf? Was he Bad?

Where would you place this evidence?

- The Big Bad Wolf called out, “Little Pig, Little Pig. Come out, come out or I’ll blow your house down.”

- How could that fact support the idea that the Big Bad Wolf is a villain?

- How could that fact support the idea that the Big Bad Wolf is not a villain? (I mean, he’s a carnivore that gave his prey an advanced warning!)

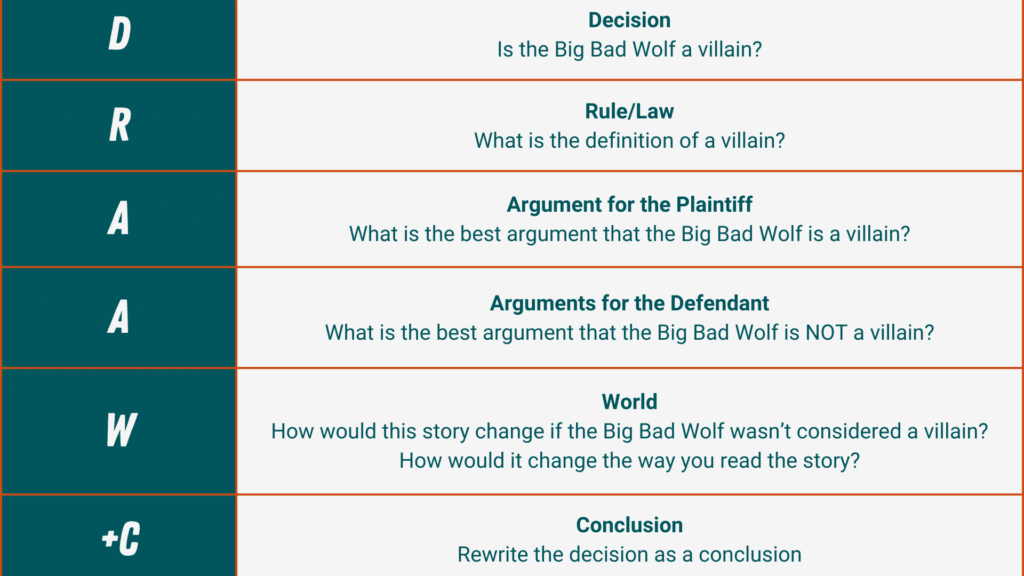

Here’s how the DRAAW+C framework would look with our Three Little Pigs example.

Increasing the Rigor of What You are Doing Already

It is not uncommon for these types of questions in our curriculum.

- What made Alexander the Great great?

- What makes the Big Bad Wolf a villain?

Introducing the analysis of evidence automatically increases the rigor of the question.

- Was Alexander the Great great? Present the best evidence from both sides.

- Was the Big Bad Wolf a villain? Present the best evidence from both sides.

Reframing the question requires thinkers to analyze a character from multiple perspectives, weigh evidence, and defend their personal position. This week, glance through your plans and see if you can incorporate this strategy with your class.

Leave a Reply